During my fourth year of medical school, someone I loved passed away from suicide. While I cycled through different stages of grief, I realized I had to stop asking myself, “What could I have done differently?” and instead start asking, “What can I do differently?”

At the time, I was also navigating the residency application process. As I traveled across the country interviewing, it became clear that the health system most passionate about suicide prevention and treating complex trauma was the Veterans Health Administration.

Fast forward to June 2020 when, in the midst of a global pandemic, I packed my bags and drove from my home in Chicago to begin my training with the UCLA-VA Internal Medicine-Primary Care program, focused on providing primary care to veterans experiencing homelessness. Suddenly, in a new city where I knew very few people, I was thrust into the frontlines of the health care workforce.

My primary care clinic every fifth and sixth week became a refuge in the midst of the relentless uncertainty I faced in the intensive care units and medical wards. During my intern year, I saw many of my veteran primary care patients more than my own family. I will never forget my veteran patients’ kindness and thoughtfulness checking in on me. Many shared stories of the uncertainty they faced when they were working on the frontlines protecting our country, and they encouraged me to keep pushing on.

While our residency didactics imparted to me medical models for treating complex trauma, the veterans I served imparted many complementary lessons and articulated two recurring needs: 1) greater access to safe outdoor spaces to heal and gain support navigating post-service life and employment, and 2) greater access to affordable fresh fruits and vegetables to support their health needs.

Photo:

(1) Dr. Peter Capone-Newton (left) talks to veteran John Raposa (right) at Care, Treatment and Rehabilitative Services (CTRS) on the West LA VA Campus

As fate would have it, a few months after I graduated from residency and had started fellowship, I was rotating at the Care Treatment and Rehabilitation Service (CTRS), a novel transitional housing program for veterans consisting of more than 140 tiny homes on the VA’s campus. When I mentioned my interests in creating healing, nature-based spaces for veterans and increasing access to fresh fruits and vegetables, the physician I was working with, Dr. Capone-Newton, looked at me quizzically: “No one’s ever told you about the Veteran’s Garden?”

Let me take a step back here. The Veterans Health Administration is the largest integrated health system in the nation serving more than nine million veterans annually. It is a single-payer health system which means that all patients are covered by the same insurer — the government. The Greater Los Angeles VA Health System (GLAVAHS) is the largest, most complex health care system within the Department of Veterans Affairs and the 388-acre West Los Angeles VA Medical Center is the most expansive care facility in the GLAVAHS.

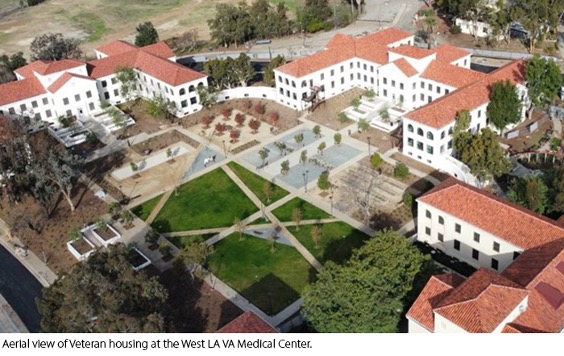

Photo:

(1) First established in 1887 as a home for disabled veterans, the West LA VA Medical Center Campus provides more than 70,000 veterans annually with access to a full continuum of health care and housing services including residential domiciliary treatment programs for substance use disorder, severe mental health, and chronic homelessness care; housing for veterans and their families; Community Living Centers (nursing home graduated care); health care; and research.

The GLAVAHS serves the nation’s largest population of unhoused veterans, and in the coming years will provide housing to more than 1,200 veterans experiencing housing insecurity. In addition to experiencing high rates of housing insecurity, veterans experience high rates of preventable disease with 87% of veterans having hypertension, 77% of veterans are overweight or obese, and one in four veterans has diabetes. Veterans also experience suicide rates more than 50% higher than non-veteran U.S. adults of the same age and sex. The Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) of veterans served at eight VA sites including the GLAVAHS found the food insecurity rate to be 24% among the population of more than 6,000 veterans surveyed, more than double the national food insecurity rate. Among veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, those who endorsed food insecurity were more likely to report binge drinking, tobacco use, less sleep, and poorer self-reported health than food-secure veterans. A national sample of veterans experiencing food insecurity had nearly four times higher suicidal ideation than food-secure veterans (39% vs. 10%), underlying the urgency of addressing veteran food insecurity.

I was shocked to learn about the Veteran’s Garden, which I had never heard of in more than three years caring for veteran patients at the VA. It turns out there is a 15-acre area of land designated on campus for agricultural therapy. If you have ever been to a UCLA baseball game, you may have seen the garden, which is just north of UCLA’s Jackie Robinson baseball field.

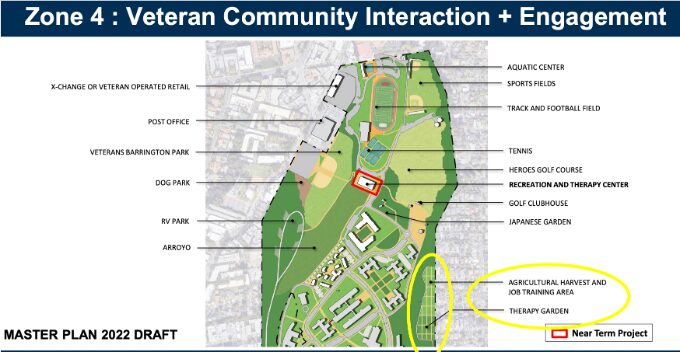

Photos:

(1) Map of North Campus from the 2022 West Los Angeles VA Campus Master Plan

(2) UCLA volunteers working in the 80 by 40 foot greenhouse in need of repair in the Veteran’s Garden

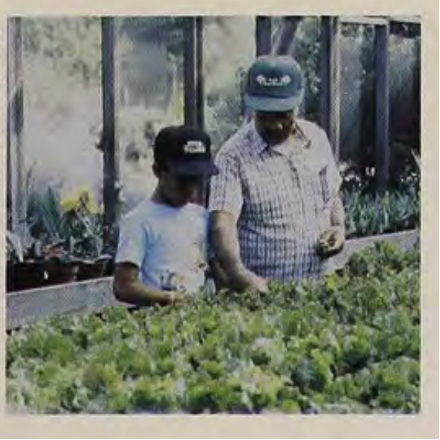

Back in 1986, a VA Occupational Therapist with previous landscaping and horticulture experience, Ida Cousino, asked the VA if there was land on campus she could use to provide veterans with therapeutic employment through agriculture. The VA agreed to let Ida use the 15-acre plot — and the Veteran’s Garden was born. The program initially mainly served Vietnam War veterans, including many veterans who were experiencing complex psychiatric illnesses including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and substance use disorder. Through individual and group therapy focused on horticultural training, interpersonal skills, and professional development, veterans experienced improved mental and physical health outcomes.

Photo:

(1) Photo from 1991 of a veteran and his son working in the greenhouse at the Veteran’s Garden

As one veteran noted, “This is where I started my healing. I almost died downtown — 30 years of drinking… Like everything down here, each and every one of us has grown. Like a plant that looks a little shaky, a little TLC is all we need.” A fellow veteran shared that the garden, “helped to rehabilitate me… I achieved some hope of getting out of my alcoholic (condition) by living around flowers.” Another veteran attested, “I saw a lot of combat. But now that I’m around plants, in a peaceful environment, I can put all that behind me.”

Photo:

(1) Jennifer Allen, GLAVAHS Whole Health Manager and Nurse Practitioner, harvests carrots from one of the garden’s 40 raised beds

While the VA previously paid two full-time directors to manage the program, when the directors retired in 2009, the roles were not re-filled and the garden was closed. This left a valuable campus resource underutilized by the VA until 2021 when the GLAVAHS Whole Health Manager Jennifer Allen began volunteering her time to restore the garden.

The Integrative Medicine Department allocates a half-day’s effort to the garden’s only paid employee, Integrative Medicine Registered Nurse Patricia Hasen, a Navy veteran and master gardener, who leads a weekly Wednesday morning “Gardening for Whole Health” course for veterans and helps maintain the garden. Many veterans are interested in attending programming in the garden beyond the Gardening for Whole Health class. However, without a dedicated staff member to operate the garden, it remains closed to veterans outside of Wednesday mornings.

The Health Equity Challenge Award would fund a one-year position to hire a Garden Manager at 80% full-time effort who could oversee planting and harvesting at the garden to fully utilize its growing potential and lead daily programming for veterans, increasing the number of veterans engaged in programming at the garden from 40 veterans annually to more than 200 veterans annually. We aim to hire a veteran to serve as the Garden Manager, as we have been very successful with our current veteran-led programming in the garden in part because of the positive impact of veteran-to-veteran peer learning.

Photos:

(1) A veteran gardener cares for a pepper plant in the garden, photo credit @LosAngelesVA Twitter

(2) A veteran gardener harvests Swiss Chard, photo credit @LosAngelesVA Twitter

Veterans are a priority group of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and we anticipate that after pilot funding from the Health Equity Challenge, we will be able to share our preliminary outcomes with the USDA and be competitive for three-year funding from the VA to continue efforts at the garden. Ultimately our hope is by 2028, after four years of tracking outcomes and having hundreds of veterans successfully engage with programming in the garden, the VA will once again restore funding to directly support staff dedicated to the garden and use all 15-acres to grow fresh produce that can be distributed for free to veterans experiencing food insecurity.

I hope through the Health Equity Challenge, we can shine a light on the profound health inequities experienced by our nation’s veterans and help inspire other civilians to get involved advancing the health of the men and women who have sacrificed so much for our country. The Health Equity Challenge’s support reviving the veteran garden will have tremendous impact in increasing access to safe outdoor spaces for veterans to heal and gain support navigating post-service life and employment, and increasing access to affordable fresh fruits and vegetables to support their health needs. Furthermore, the Health Equity Challenge would provide seed funding that will hopefully catalyze the restoration of operations throughout the entire 15-acre farm which, once functional again, will be the largest working farm integrated within a health system in the nation and a model nationally for Food is Medicine initiatives.

Photo:

(1) All smiles with Jenn Allen, and our collaborators, John Emmons, an Army veteran, and his wife Emily Emmons, who together founded Ho’ola Farms to promote healing and connection for veterans living in Hawai’i, and Chef Alice Waters who, along with Jaemie Ballesteros Altman of the Hammer Food Project Foundation, have been incredible mentors and supporters of the Veteran’s Garden.

I invite you to join us in planting the seeds of a food and health system movement in Los Angeles that can support the health of veterans and civilians across the nation.

By Katie Fruin

2024 Health Equity Challenge Finalist

Katie Fruin, MD, is a recent graduate of the UCLA Internal Medicine VA-Primary Care program and currently pursuing her Master of Science in Health Policy and Management at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health through UCLA’s Preventive Medicine fellowship.

continue reading

Related Posts

Hi, I’m Amani. I’m a third-year medical student at UCLA, a former high school science teacher, a published short story writer, and (hopefully 😊) a future neurosurgeon.

When I first saw Brea at the LA animal shelter, her white-gray checkered fur was overgrown and severely matted.

I find myself standing on a winding path, fraught with the fears and uncertainties that have long shadowed the dreams of my community.